By Dr Brighton Chireka

The Pandemic

In late December 2019, a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown origin were reported in Wuhan China, with the seafood market being identified as the source. The World Health Organization was informed promptly and the outbreak spread rapidly, leading to a global pandemic declaration by March 11th, 2020. Recording cases proved difficult, as frequent changes to the case definition resulted in variable numbers of cases detected. In addition, there was limited testing for COVID-19 in the UK at this time, affecting analysis which largely relied on mortality rates. This likely underestimated cases as it did not include mild or asymptomatic ones. Upon news that Dr Li Wenliang, an eye specialist working at Wuhan Central Hospital in China, died of COVID-19 on 7th February 2020, healthcare workers around the world were alerted to the danger they faced. The announcement that 1716 healthcare workers had been infected and five had died in China further highlighted the urgent need for protection for frontline workers in this fight against the outbreak.

Plight of health workers

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the responsibilities and vulnerabilities of frontline healthcare workers, as many who signed an oath to save lives put themselves at risk. This paradox revealed a moral and legal duty on governments to protect them. When the virus hit the UK, anxiety levels among its ethnic minorities rose sharply due to lack of information, perceived and real segregation and leadership gap. There was a lack of leadership and ownership when it came to supporting the ethnic minorities, leaving them waiting for someone to take action which ultimately no one did.

Leadership vacuum

In response to the lack of leadership and support for the ethnic minorities affected by COVID-19 in the UK, I woke up one morning and spoke out about the plight of ethnic minorities in the UK, which struck a chord with many. The video that I did highlighting the plight of ethnic minorities in the UK went viral as it resonated with thousands of people. This led to an influx of comments, questions and pleas for help. Recognising a leadership vacuum, My friend and mentor Professor Kunonga and I stepped up to fill this leadership vacuum, calling for an online meeting to create a safe space for people to share their experiences. We did not seek any approval or titles – only the chance to help.

Zoom meetings

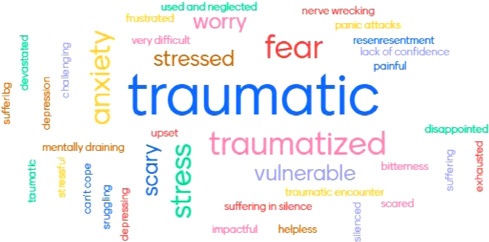

At our first zoom meeting, we were humbled by the response of the community, with over 400 people joining. People poured out their emotions and experiences without any interruptions or criticism. Everyone was respectful to each other and listened intently, though there wasn’t enough time to hear from everyone who wanted to speak. We went into the meeting with humility, knowing that we had no solutions but believing that by coming together, we could come up with a solution to our challenges. While the meeting was initially intended to be a one-off, it became clear that an open dialogue between attendees was necessary to come up with solutions to the challenges they faced. We focused on listening only at the first meeting. We decided not to offer solutions during this first meeting for two main reasons. Firstly, we wanted to understand the problems people were facing before offering any solutions. Secondly, for any intervention to be successful it must be accepted by the community who are supposed to benefit from it – so getting buy-in is vital. By listening and engaging with the community in this way, we hoped that our interventions will be more successful in helping people cope with the impact of COVID-19 pandemic.

Compassionate leadership in the community

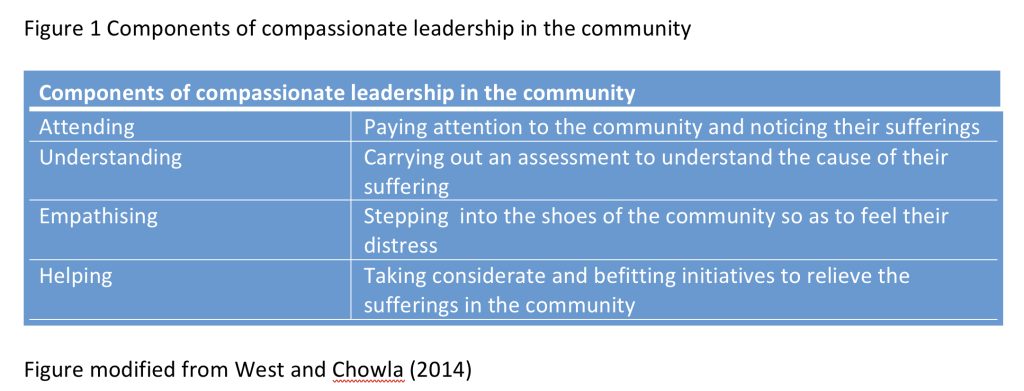

We employed a compassionate leadership style when engaging with the community. We listened carefully to people’s experiences, including their pain and emotions. We sought to understand their challenges, hopes, and wishes by putting ourselves in their shoes. To ensure everyone was comfortable sharing, we allowed people to email us with their thoughts and suggestions if they were not confident enough to do so publicly. After listening for three weeks over several two-hour meetings, we discussed how best to help each other. The way we listened demonstrated our commitment to understanding the community and providing them with the support they need. See figure 1.

Helping the community after listening

It was decided that weekly Zoom meetings were essential in order to address issues identified during listening sessions, such as stress management, leadership, career progression, racism, speaking up and out, accessing professional support and taking advantage of allyship. Prominent experts with knowledge of each subject were invited to provide guidance to the community for free, despite their busy schedules. Prof Dame Elizabeth Anionwu, Professor Dame Donna Kinnair, Eden Charles, Roger Kline, Prof Aliko Ahmed, Prof Rotimi Jaiyesimi , Dr Titilola Banjoko. Yvonne Coghill and various others spent at least two hours talking to the community and providing invaluable advice.

During the Zoom discussions, it became evident that the lack of clear leadership and uncertainty in the workplace due to COVID-19 had caused anxiety and moral injury, with heavy workloads leading to mental ill-health. Furthermore, participants discussed being unable to travel home in times of illness or death, and feeling doubts or mistrust towards their workplace leaders. To cope with these issues, they looked towards spirituality, peer-to-peer support and community support. Sharing these experiences in a safe space on the Zoom forum was found to be therapeutic.

Contribution to research

The weekly Zoom meetings ran for nine months, during which Dr. Mbiba worked to capture the experiences of the community and publish a paper titled “At the deep end: COVID-19 experiences of Zimbabwean health and care workers in the United Kingdom” in the Journal of Migration and Health. The platform expanded in collaboration with Better Health for Africa, Zimhealth UK, and many other ethnic minorities in the UK, forming many groups to support its vision and values. These stories will be featured in a book to be published later this year.

It is my conclusion that compassionate leadership was found to have made a huge difference in creating safe spaces for people to share their experiences and find solace during the pandemic. It also led to the formation of Zimbabwe Nurses and Doctors Associations in the UK. Furthermore the UK government recognised the importance of ethnic minorities leaders and worked with them to address vaccine hesitancy and increase uptake, as well as launching an enquiry into its handling of the pandemic that includes input from these communities. It is argued that compassionate leadership does not require power, but passion for making a difference, which we would like to hear more about from those who attended our weekly Zoom meetings or other minorities who managed during the pandemic.

![]()